Functional luciferase design with deep learning

16 Aug 2023Written in late Mar 2023, a quick review of de-novo enzyme design with deep learning from David Baker’s group. Christian Dallago and Kevin Yang wrote a fantastic Nature News and Views piece a couple months later, describing the technique with some more depth.

A deep-learning-based “family-wide hallucination” approach generates idealized protein structures for designing artificial luciferases with high selectivity and thermostability, enabling the creation of highly active and specific biocatalysts with broad biomedical applications.

De novo enzyme design has been a grand challenge in biology, as it seeks to create tailor-made enzymes that overcome the limitations of naturally occurring ones. The complexity of protein sequence-structure relationships and the scarcity of suitable protein structures have made it a difficult task. However, breakthroughs in computational methods and deep learning approaches are starting to unlock the potential of de novo enzyme design, paving the way for the development of highly specific, efficient, and stable biocatalysts that can revolutionize various fields, including biomedicine, environmental remediation, and industrial biotechnology.

Luciferases are a particular enzyme of interest, as they catalyze the oxidation of luciferin substrates, producing bioluminescent light that is widely used in bioassays and biomedical imaging. Their ability to generate luminescent photons without the need for an external excitation light source results in higher sensitivity and reduced autofluorescence or phototoxicity in live animal models and biological samples. However, the development of luciferases as molecular probes faces several challenges, including the limited number of native luciferases identified, structural instability due to multiple disulfide bonds, poor recognition of synthetic luciferins with more desirable photophysical properties, and low substrate specificity, which hinders multiplexed imaging for tracking multiple processes in parallel. Building on a growing body of knowledge regarding protein structure prediction 1, 2 with deep learning and small molecule-protein docking 3, Yeh et al 4 chose to design luciferases. The authors show that they can leverage deep learning to design luciferases that are small, highly stable, well-expressed in cells, substrate-specific, and need no cofactors to function.

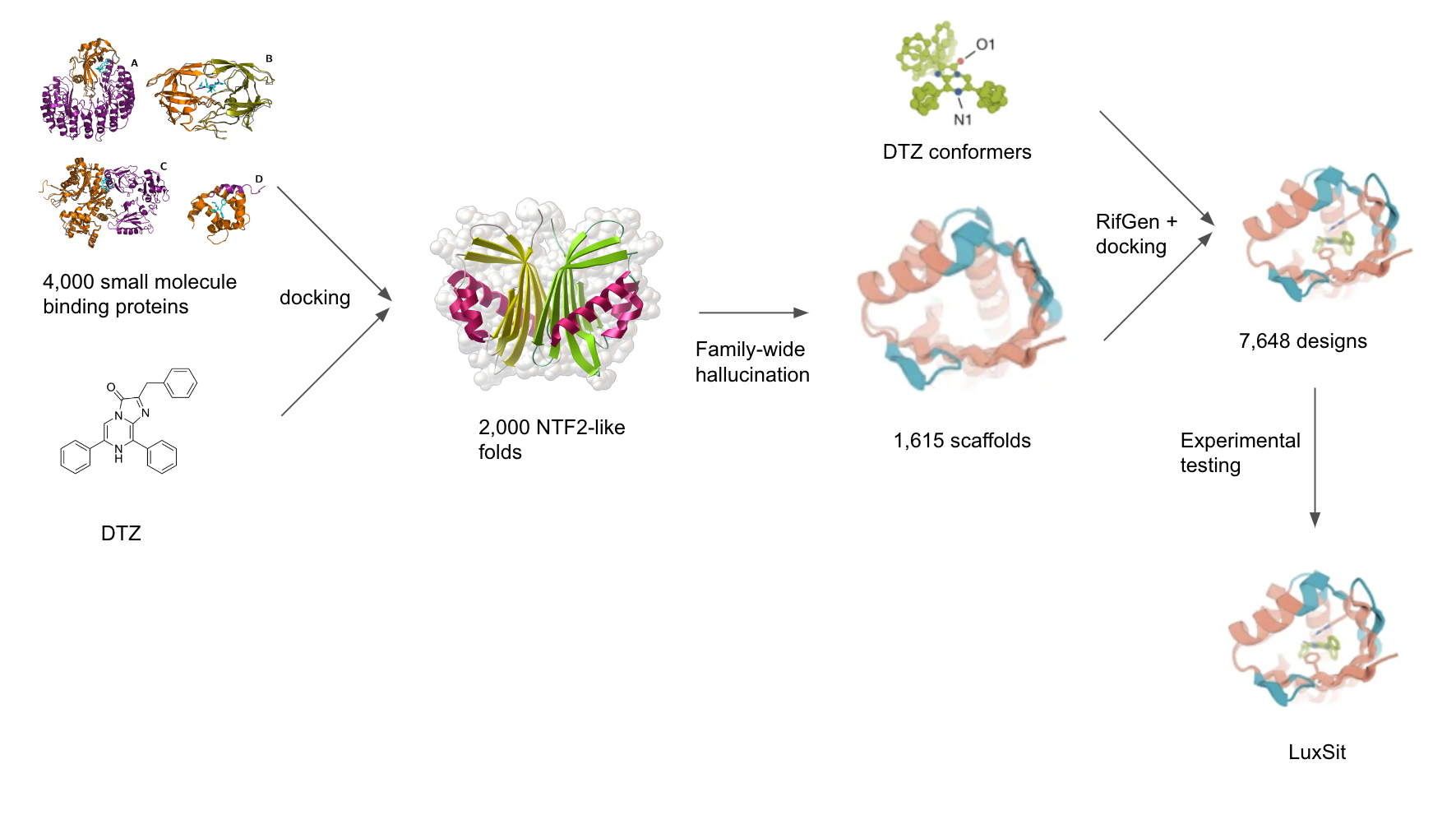

Yeh and colleagues chose a synthetic luciferin, diphenylterazine (DTZ), as the target substrate because of its high quantum yield, red-shifted emission, favorable in vivo pharmacokinetics, and lack of required cofactors for light emission. Few native structures with favorable binding pockets to DTZ exist, so a computational screen was performed to identify a greater number of protein scaffolds. They computationally docked DTZ into 4,000 native small-molecule-binding proteins, and found that nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2)-like folds have binding pockets with appropriate shape complementarity and size for DTZ placement.

Using the NTF2-like superfamily as the target topology, the authors selected 2,000 naturally occurring proteins within the superfamily. They sought to generate more proteins with the desired fold using “family wide hallucination”, since native NTF2 structures have features that are not ideal such as long loops that compromise stability. They conducted a Monte Carlo search in sequence space, guided by the predicted structure confidence and a topology-specific loss function over core residue pair geometries. This resulted in 1,615 hallucinated NTF2 scaffolds with greater shape-complementary binding pockets for DTZ than the native small-molecule-binding proteins, as measured by RIF binding energies.

A schematic representation of the family-wide hallucination approach to design a novel luciferase taken by Yeh et al.

A schematic representation of the family-wide hallucination approach to design a novel luciferase taken by Yeh et al.

Yeh and colleagues sought to design an effective active-site into their generated protein scaffolds. Using insights from quantum chemistry calculations 5 and experimental data 6, they designed a shape catalytic site that stabilizes the anionic state of DTZ and lowers the single-electron transfer (SET) energy barrier. To this end, they generated anionic DTZ conformers and used the RifGen 7, 8 method to generate rotamer interaction fields (RIFs) of preferred configurations of the scaffold amino acid residues based on their hydrogen-bonding and nonpolar interactions with DTZ. 50,000 docks with the most favorable interactions with DTZ were chosen for further sequence optimization using RosettaDesign 9. Interestingly, Yeh and colleagues used RosettaDesign to optimize the remainder of the sequence instead of ProteinMPNN 10, which was used in their work to design (h-CTZ)-specific luciferases. These designs were then filtered down to 7,648 proteins on the basis of ligand-binding energy, protein-ligand hydrogen bonds, shape complementarity, and contact molecular surface.

This protein library was cloned into E.Coli for expression and screened for bioluminescent activity. The activity of selected colony clones were confirmed by a 96-well plate expression. 3 active designs were identified; the top named LuxSit. Using circular dichroism (CD), the authors found an organized α-β structure for LuxSit. CD melting experiments further showed the protein was not fully unfolded at 95°C, indicating thermal stability.

LuxSit was further optimized using site saturation mutagenesis, in which each residue in the substrate-binding pocket was mutated to every other amino acid. This analysis led to further optimized LuxSit variants, dubbed LuxSit-i and LuxSit-f, with catalytic efficiencies comparable to native luciferases. The authors also purified LuxSit for size-exclusion chromatography which indicated that it is a single, uniform entity without forming any aggregates or multimeric complex. Yeh and colleagues then tested expression of LuxSit-i in live mammalian cells. They found that their engineered protein has high substrate specificity, an impressive feat compared to promiscuous native and previously engineered luciferases which act on many luciferin substrates.

Computational enzyme design has been constrained by the number of available scaffolds. Using deep learning to produce a large number of de-novo designed scaffolds, Yeh et al were able to design a novel luciferase with desirable biophysical characteristics for use as a biological probe. In conclusion, the development of the family-wide hallucination method has significant implications for protein engineering and catalysis research. By generating a vast number of de-novo-designed scaffolds, this approach opens up new possibilities for identifying potential substrate-binding and catalytic residues, even in cases where the reaction mechanism is not fully understood. The ability to explore a wide range of structural and catalytic hypotheses with shape and chemically complementary binding pockets, but different catalytic residue placements, could greatly enhance our understanding of enzyme function and lead to the design of novel and more efficient catalysts.

References

-

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). ↩

-

Minkyung Baek et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 373, 871-876(2021). ↩

-

Cao, L. et al. Design of protein-binding proteins from the target structure alone. Nature 605, 551–560 (2022). ↩

-

Yeh, A.HW., Norn, C., Kipnis, Y. et al. De novo design of luciferases using deep learning. Nature 614, 774–780 (2023). ↩

-

Ding, B. W. & Liu, Y. J. Bioluminescence of firefly squid via mechanism of single electron-transfer oxygenation and charge-transfer-induced luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1106–1119 (2017). ↩

-

Branchini, B. R. et al. Experimental support for a single electron-transfer oxidation mechanism in firefly bioluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7592–7595 (2015). ↩

-

Dou, J. Y. et al. De novo design of a fluorescence-activating β-barrel. Nature 561, 485–491 (2018). ↩

-

Cao, L. et al. Design of protein-binding proteins from the target structure alone. Nature 605, 551–560 (2022). ↩

-

Yi Liu, Brian Kuhlman, RosettaDesign server for protein design, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 34, Issue suppl_2, 1 July 2006, Pages W235–W238 ↩

-

J. Dauparas et al. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN.Science378, 49-56(2022). ↩